Yes is more than a word. It’s a state of being, of relating, and a gateway to curiosity, growth, and resilience, according to internationally recognized educator, neuropsychiatrist, and bestselling author Dr. Dan Siegel. He and co-author Tina Payne Bryson have written a new book that offers parents everywhere a roadmap for developing and growing their child’s inner spark and internal compass to guide them throughout their lives. It’s called, “YES Brain: How to Cultivate Courage, Curiosity, and Resilience in Your Child.”

Lu Hanessian: This is an important message and book. All parents want to raise kids who feel an inner sense of stability and authenticity, who can cope with life’s disappointments and losses, who know themselves, and who care deeply about others and themselves. I think most people would say that’s a no-brainer! Actually, you and Tina would say it’s a “yes brainer.”

Dan Siegel: It’s a yes-brainer, exactly! The idea is that when parents or anyone caring for a child—a grandparent, a coach or a teacher—anyone who’s supporting the growth of children, when they understand that the brain can get into a “yes brain” state and approach life with all of these positive features versus a “no brain” state, which is created when we feel threatened and we shut down, you’re actually empowered as an adult to help raise children where these states of a yes brain that are repeatedly created become a trait of positivity in life.

Lu Hanessian: So, a “yes brain” is open, it’s flexible, it can pause before reacting, all that good stuff, looks at the glass half full, or maybe filled and overflowing and “no brain” is…

Dan Siegel: “No brain” is where you’re either getting ready to fight or you might get ready to flee and even, you don’t know whether to fight or flee, so you freeze up your muscles and hold on until you figure out whether you’re going to run or fight and those are the activating threat states of a no brain. There’s also a deactivating no brain threat state which is where you collapse in a faint. So whether you’re fainting or moving toward the freeze or flee or fight, all of those are called reactive states that are activated. For example, if I said “No” harshly several times, you’d feel that kind of reactivity rising up in you depending on your temperament and your history. You might tend to go to fight, you might tend to faint. We’re all different from each other, but in any of those F’s of a no brain state, you shut down learning and you shut down connection to other people. When it’s repeated in a child, a child’s development becomes curtailed because they’re not open to new learning and connected with others.

Lu Hanessian: I’ve been at conferences where I’ve heard you speak and do that yes/no exercise you just referred to and it’s incredible how the collective reaction of the “No” you repeat where people said they felt frightened or small or closed or rigid, and, collectively, people said that “Yes” made them feel ‘open, free, safe, and trusting.’ So if we think of these as states that our child could get into in relationship with us, I think parents might translate that to: “I feel connected,” “My child is easy to approach or get along with,” or, I think with no brain, a lot of parents kind of head into that “Oh, he’s so stubborn or judgmental,” but this affects parents, too. Parents have a yes brain and a no brain, as well!

Dan Siegel: Well, exactly Lu, and it’s so beautiful to hear you remember workshops you’ve been to where I do the “No” experience and the “Yes” experience, and when parents have the opportunity—which is basically where the idea of the book came from—to distinguish these two in themselves, they learn from direct experience that a no brain can be activated when we’re frustrated, when we’re feeling at the end of our rope, when our kid pushes our buttons, when something at work isn’t going right, a neighbor is doing this or that; there are so many things that can get us into a no brain state. And when you as a parent are yourself in that state, you can’t do good parenting when you’re in a reactive no brain state, when you’re fighting with your kid, wanting to run away, when you’re freezing up, or even collapsing in a faint, all of these reactive states shut down good, open, receptive parenting.

Instead you want to learn to move yourself from a “no brain” state you might be in to a “yes brain” state of receptivity where it’s all those things you just described, openness, a sense of connection, curiosity. There’s a positive approach to life that comes, when you look at the neural circuitry of the yes brain, a way you learn a challenge is an opportunity to learn more, not to collapse in fear, that a difficulty you’re having with a friend or family member is an opportunity to get closer, rather than just fight back and hold a grudge. All of these yes brain approaches are, in many ways, the foundations for what Carol Dweck calls a growth mindset or Angela Duckworth would say is the component of grit, of having this resilience, to be in a positive mindset, where you look at difficulties and say, how can I learn from this.

Lu Hanessian: The book walks parents through four yes brain fundamentals as you and Tina call them. The acronym is BRIE. The B is balance, the R is resilience, insight is I and empathy is E. So just do a quick summary of each, because altogether, you make a really compelling, science-based case that BRIE is a growth-oriented process that reinforces itself, that the more we cultivate this process, it cultivates good things in us. It leads to an integrated brain and that integration creates more integration.

The 4 elements of a yes brain

1) balance — the state of receptivity that allows us to embrace the whole range of our emotional experience

2) resilience — the capacity to shift from reactivity to receptivity and come back to balance

3) insight — awareness of our own internal state that cultivates understanding of ourselves and others

4) empathy — the sensations and feelings we get in response to others’ emotions as well as the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person

Dan Siegel: B stands for balance. And the balance term really means, when you’re embracing the wide array of feeling states you can have, the emotions that arise, the sense of meaning of things, sometimes positive sometimes negative, not pushing things away but actually holding them in awareness with balance. It’s a kind of receptive state to your own variety of emotional experiences you can have, so you’re open to the whole rainbow of emotions rather than saying I’m just going to have one or the other. So that’s a way of thinking about integration that allows the brain to grow in such a fashion that instead of being frightened of intense emotions, you learn to surf the wave of emotions. When you can sail the ship of your mind through your body’s experience with emotion, all these things that arise, they allow you to really come to life with a lot of strength and that’s what balance means.

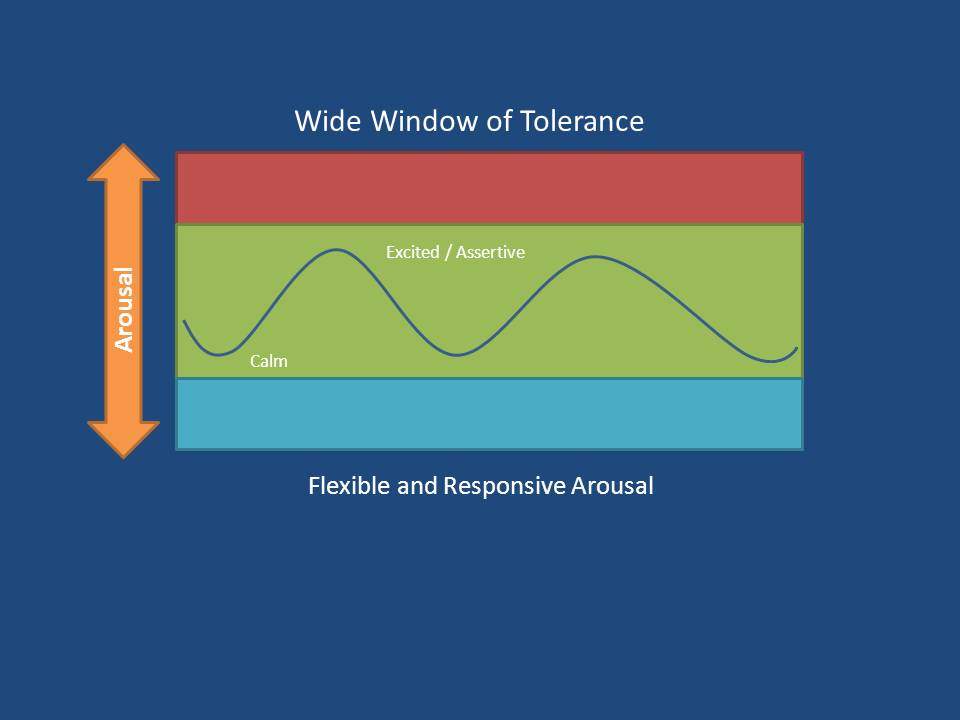

Lu Hanessian: You give a lot of really great strategies in each one. Let’s just touch on one: the red zone, green zone, blue zone, where you teach kids and parents how to recognize when they’re becoming hyper-aroused or hypo-aroused, just basically learning to check in, and see when they’re becoming reactive.

Dan Siegel: A green zone is this band of experience, the width of intense emotions that are either low or high, that you can stay floating beautifully down this river. Sometimes those emotions get so upsetting, you get chaotic and that’s the red zone, and sometimes they get so shut down that you’re unable to be flexible, and that’s the blue zone. The green zone is right in the middle, it’s this window of tolerance—in science, that’s what we talk about. When you translate that for a parent, you can teach a child or an adolescent to be aware of which zone are they in, and to widen their green zone—let’s say for an emotion of frustration or fear or sadness or even anger, yes, you can experience these same emotions, but now you remain balanced, which is basically a synonym for integrated. You remain integrated while you’re experiencing an emotion, whereas before, it really threw you. You don’t have the skills yet to deal with anger or fear, let’s say, and so we give lots of techniques for how to teach a child to stay present with their emotion and widen that green zone.

Lu Hanessian: And so, mindful of our child’s window of tolerance, then, we can expand it together. But then, expanding the green zone itself is so interesting. You talk about cultivating resilience and how we can expand this really wonderful green zone. When we’re in that space, how do we widen it, deepen it, so that the more we become mindfully present with our child, the more we promote our own yes brain. It’s almost that we’re co-creating that resilience, isn’t it?

Dan Siegel: Exactly. Resilience can be thought of as, when I leave the green zone and I’m in red or blue, how do I get back to balance? And the way to think about that in terms of what you can do as a parent is this: When your child is in the red or blue zones, out of this green area of balance, in that moment, they’re in a reactive no brain state. So you have worked with them to feel what that feels like, and that essentially to “name it to tame it” is the term you can use where literally, by identifying a state you’re in, “I’m really really angry and I’m in the red zone” or “I’m really really frightened and I’m in the blue zone.” When you name it, research shows, you’re actually allowing the brain to go from huge amounts of firing or being shut down—the red or the green, the red or the blue—and now you’re helping with the naming it and identifying it, and being aware of it, moving toward the green zone. Now, you may say that’s kind of like magic. The way to think about it is when you as a parent are tuning into the state of your child, that child who is alone in their dysregulation, that is in the red fired up or blue shut down, in connecting with you, that dyad or pair, that interaction of two people, allows that child to use you as a resource in this moment to go, “Oh I can go from the red back to the green.” You may give them some space, sensing a few breaths, stretching, walking around, having a drink of water, there’s…regulated. You’ve basically taught your child, number one, be aware of your state. So when you’re in a no brain state, just know that’s where it is. You don’t have to get mad at yourself, just know that’s where it is.

Number two, when you’re out of balance, when you’re in this “no brain” state, you can come back to a “yes brain” state, the green zone. And here are the techniques your parent has taught you. They take a break, get a drink of water, put a hand on chest, hand on the belly, sense the breath, and they do what they’ve learned to do as a skill, to go from the no brain state to the yes brain state, they’ve gone from reactivity to receptivity, and you’ve taught them the skill of resilience.

Lu Hanessian: In the process of teaching them the skill of resilience, we are also developing insight, the I in BRIE—insight into themselves and into ourselves. One of the goals and benefits of living, loving, and raising our kids more mindfully is developing the ability to look within, to observe ourselves and understand who we are in relationship and in the world.

Dan Siegel: Exactly. For me, both as a dad and just as a human being on the planet, learning to be kind of aware, and it brings up the insight notion, aware of your own internal state, allows you to see that we’re not alone in this world, we’re very relational beings. And so the insight into your own internal state, like “Am I in balance?,” the B, or “Am I off balance and need to get back.” The need for resilience, your insight comes in here because you can say, well, “What I need to do now is to connect with another person, or even myself?” I begin to feel that life is okay, that if things are not so good right now, I’ve learned from experience that even if I’m in a distressed, imbalanced state, I have the experience that I can get back to balance. You use these deep connecting experiences to teach the skills of insight and also to teach how you can use these ways of changing your state to become more resilient.

Lu Hanessian: And these are all the building blocks of empathy, the E in BRIE. In your teachings, you’ve often shared another acronym SNAG which stands for Stimulate Neuronal Activation and Growth. Since what we practice grows, can you share a little about how a parent can SNAG a child’s brain to cultivate empathy?

You don’t have to be a neurosurgeon to help create an integrated, structurally strong brain in your child. You have to have a relationship that inspires them to rewire their brain toward integration.

Dan Siegel: Well thanks for reminding me of my acronym addiction! We’ve gone from cheesy brie to active snagging. The idea there is where attention goes, neural firing flows and neural connection grows. What that means is that where you help a child focus attention, like on their internal state or for empathy on the state of another person or family member or yourself —“Here’s what I’m feeling right now”—you’re stimulating neuronal activation. You don’t have to be a neurosurgeon to help create an integrated, structurally strong brain in your child. You have to have a relationship that inspires them to rewire their brain toward integration.

You stimulate neuronal activation, that’s where attention goes. You’re helping focus attention, neural firing flows, and here’s the secret to the next part of that little ditty: Where attention goes, neural firing flows and neural connections grows and that’s the G of SNAG. And what that means is that, and it’s absolutely fabulous about neuroplasticity, is that energy and information flow is what’s directed by attention, so our relationship, which is where we share that flow, can actually shape our child’s brain, stimulate neuronal activation in those circuits that are activated, turn on genes, create proteins and actually strengthen their physical and anatomical connections to each other! It’s a fun acronym because it reminds you as a parent that you have the empowerment to figure out, how do you want to snag your brain? If you’re a parent, the question is how do you want to help snag your child’s brain. And the answer is toward well-being. And then you go, “Well how do I do that?” And that’s toward integration and that’s what the “yes brain” is all about. How do you create an integrated “yes brain” state so that repeated states that are created when your child is growing up with you become traits of positivity in the child’s life? A state becomes a trait because of snagging the brain.

Lu Hanessian: I once heard you say, “Integration is kindness made visible.” And I thought that’s such a beautiful concept that is equal parts hopeful and hard science.

Dan Siegel: Exactly. I say yes to that!

Lu Hanessian: Alright two more questions, one that I know parents everywhere are going to be curious about…setting limits. “YES Brain” is not of course about permissiveness. It’s not about saying yes all the time. Is it that when we promote our own “yes brain” we can set limits and say no and respond with flexibility and be confident in our choices all with an open-hearted stance, in other words, we can say no with a yes spirit? We can say no with kind of a yes energy.

One of the biggest issues with a book called the “YES brain” is that people think, “Oh, permissive parenting.”

Dan Siegel: One of the biggest issues with a book called the “YES brain” is that people think, “Oh, permissive parenting” and that’s not at all what we’re saying. When a child has the experience of structure and they get freedom from structure and Tina Bryson, my coauthor and I, we totally embrace the importance for structure, for thinking of the word discipline as teaching and that when a child learns from your teaching that structure is their way to gain freedom and they learn the experience of that, then the “yes brain” approach to parenting is saying something like this. Let’s do a simple example: a child is asking for ice cream before dinner, and you say “No way! That’s the stupidest thing I’ve heard all day that is dumb!” So that would be one response. Here would be another one. “Can I have ice cream before dinner?” “Are you out of your mind?! How many times are you going to ask me something as ridiculous as that?!” Versus this: “Can I have ice cream before dinner?” “You know, I’m hungry too and ice cream before dinner sounds like such a cool idea. We need to eat our dinner first, and then, you know something, I’m so in the mood for vanilla. But why don’t we figure out which flavor we’ll get later. Let’s have dinner and we can plan on when we’ll get the ice cream together.” So you’ve heard the request—I call it PART, another acronym—you’re present for the request, P, you attune to the feelings behind the request, you resonate with it, you go, “Hey I’d like to ice cream too, I’m with you”… you develop the T trust. And then you say “No, we’re not having ice cream.” But I love the feelings behind the request. And it is totally understandable for you to ask for it so let’s figure out a way to share our love for ice cream after we eat the nutritious food. So that’s an example where you’re creating structure and you’re teaching a child that they can express their desire and how they’d like something to go. You’re creating structure and saying “No, it’s not going to go that way,” but the desire behind your request I see and the feeling is a feeling I can even relate to. So that’s the yes brain approach while being given structure and putting limits that we don’t eat ice cream before dinner.

Also in this podcast:

- Helping kids create more meaningful lives

- What do I want for my child? Investigating measures of success and happiness

- Navigating “yes brain” parenting into later years

Lu Hanessian was part of the first cohort of one hundred international students enrolled in Mindsight Institute’s online Interpersonal Neurobiology certificate program taught by Dr. Daniel Siegel.

The post Dr. Dan Siegel: What Hearing “Yes” Does to Your Child’s Brain appeared first on Mindful.

from RSSMix.com Mix ID 8196908 https://www.mindful.org/dr-dan-siegel-hearing-yes-childs-brain/

No comments:

Post a Comment